The weight of the world on seventh-grade shoulders

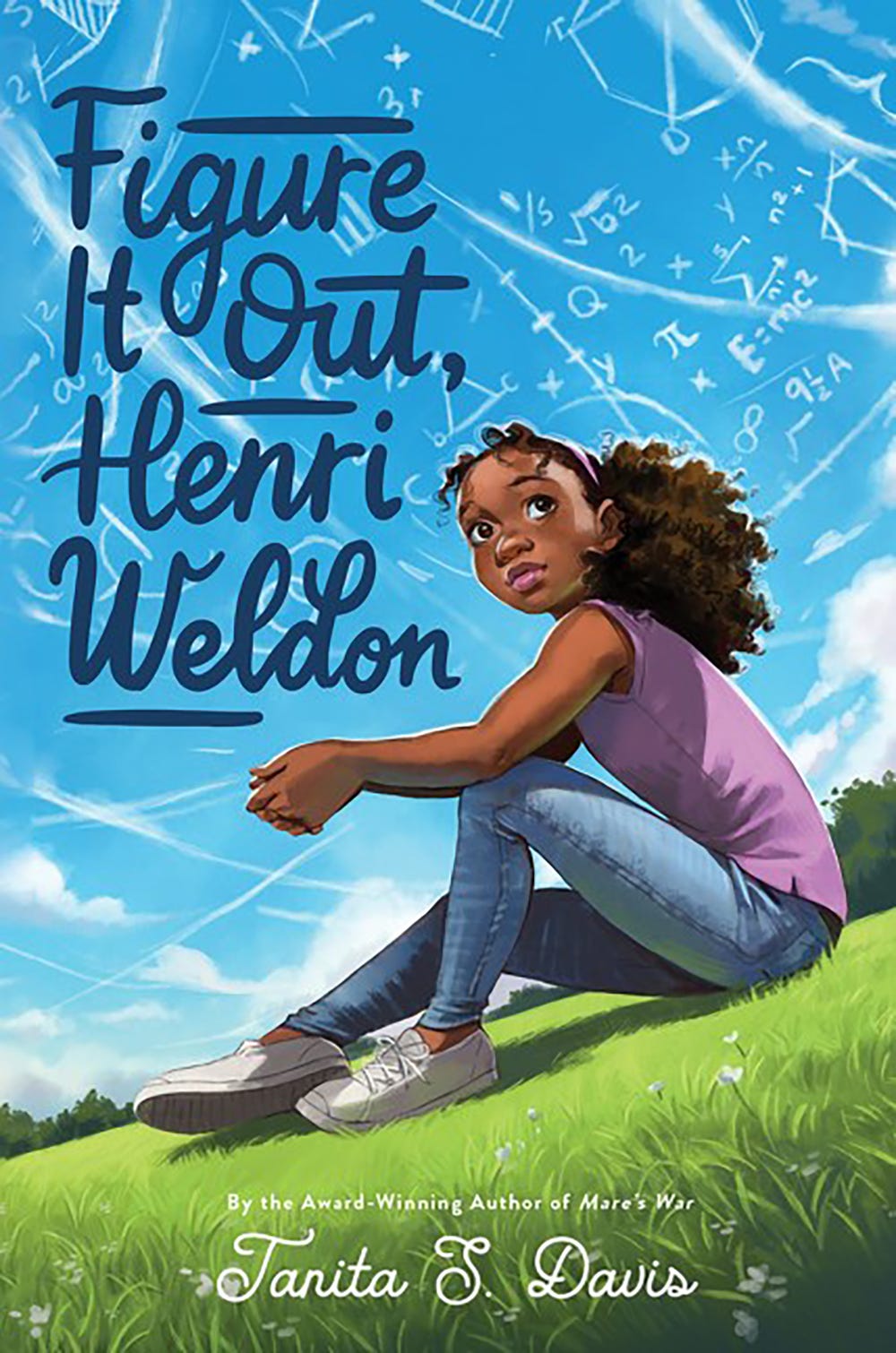

Tanita S. Davis' Figure It Out, Henri Weldon

“If she’s going to succeed, she doesn’t need fun, she needs to apply herself,” Mom turned to her younger sister, her voice taking on a dangerous edge. “I know I can’t expect you to understand.”

Everything stopped. Henri’s stomach lurched, and even Kat sucked in a breath.

—Figure It Out, Henri Weldon, by Tanita S. Davis

Hello again, my friends,

I’m running around the house getting ready for another work week—I always tell myself I’m going to prep before now, but never seem to manage it—so I’m just going to dive right in to this gem of a book.

Seventh grader Henri Weldon is switching schools. She’s leaving the special education school she’s been at for the local public school. The school and her parents are very involved—there’s a plan in place to make sure that Henri’s transition goes smoothly. Henri is pretty anxious about the whole thing—she’ll have a math tutor, but her dyscalculia makes numbers challenging in general, which will affect figuring out a new building and paying for lunch. But her older sister will be there, and even with the anxiety, she’s excited, too.

Henri gets along great with her tutor, and through him, makes friends with his siblings… and that’s where the trouble starts. Because Henri’s sister can’t STAND his family, and she’s so angry that Henri is friendly with them that she flat-out stops talking to her. Which means that Henri is suddenly largely flying solo at a new school.

She makes do. She discovers that she loves poetry. And soccer. And that she’s really good at both—but on top of her schoolwork, she’s suddenly got a lot to juggle. It isn’t long before she’s feeling like she’s taken too much on, that she’s spread too thin, but she doesn’t want to give up the things that she loves OR let her family down.

Once again, everyone had something to say about what Henri was doing. All she got was bossy comments and unasked-for advice. Nobody had even asked Henri if she was excited to be playing or felt ready for the game. They only worried that she wasn’t.

—Figure It Out, Henri Weldon, by Tanita S. Davis

Where to even start? I loved this one. Prepare for verbal flailing.

It’s a new kid in school story. It’s a family story. It’s a story about figuring out what’s important to you, realizing that those important things aren’t necessarily the same things that are important to your loved ones, and figuring out how to navigate that.

Which is all very BIG STUFF. Cripes, as ADULTS we struggle with those issues. Worrying about not being good enough, about being a disappointment. Feeling misunderstood. And really, not just feeling misunderstood, but being misunderstood. Feeling like an outsider in your own family. Craving a different sort of connection and support than the people closest to you can provide.

This is all very heavy stuff, but this is not a heavy book—the BIG STUFF here comes from the book’s emotional honesty, but the story itself is gentle and warm and empathetic and funny. There are no villains here: even when characters hurt one another, it’s usually unintentional and because of differences in perspective.

Everyone, regardless of age, is TRYING.

It’s a story about kids and parents hitting a divide, and then finding each other again. About working to start to understand themselves and one another. About overcoming differences of personality; about accepting that different people are driven by different things, have different priorities. It portrays different family structures, different ways of showing love and support, different emotional needs. It shows how clashes and misunderstandings and hurt come out of all those differences—and how, with work, those clashes can be overcome.

It was fine, though, Henri reminded herself. She’d said she would do this whether or not anyone noticed. And there would be another game.

—Figure It Out, Henri Weldon, by Tanita S. Davis

Over the course of the book, Henri comes into her own at school. She realizes that what is important to her is not necessarily important to the rest of her family—she explicitly recognizes and sees that, and she accepts it. It makes her sad, but she accepts it—and the miracle here is that her family recognizes it, too. They see it, they see that she sees it, and because of that realization—and, I’d assume, some serious off-screen soul-searching—they take steps to start the process of improving communication and acceptance and healing. It’s lovely, and yes, it made me cry.

Once last thing! (Thank you for bearing with me. As usual, I always have trouble articulating when I love a book so very much.) This book is all about mother-daughter and sister-sister relationships. We see how Henri’s relationship with her mother parallels her mother’s relationship with Henri’s aunt, and it’s easy to extrapolate that her mother and aunt’s childhood relationship parallels Henri’s relationship with her older sister.

It’s nuanced and real and so, so smart—it shows how some of those childhood hurts and disconnects can carry over into adulthood, how they can affect relationships across multiple generations. It shows how we can hold resentment AND wholehearted love towards the same person. It’s beautifully done, and the reason it works so well is because the characters are treated with such love and care.

Full disclosure: Tanita and I have known each other, mostly online, for approximately a billion years, and she is a person of my heart. That said, I’m 99.999% sure I would have loved this book just as much even if I didn’t have oodles of affection for its author.

I hope you all have a fantastic week.

More soon,

Leila

Mmmm, sounds like a good one...

Well, THIS was wholly unexpected!

I'm so glad you enjoyed Henri! I am always so happy to read about people really GETTING my books.

We experience as children that people can only give us what they have to give, but it's not something that we often can articulate explicitly; we often don't have the language to talk about feelings of being slightly Other in our early spaces, spaces which for others seem to be wholly sufficient for them to be deeply rooted and grow. The misunderstood/outsider thing you noted is also tied up, for me, in the idea also of the "you have to work twice as hard" narrative spoken in Black and immigrant communities - what happens if you're one of those people for whom working twice as hard will STILL not get you half as far? What then? So much of "conventional wisdom" doesn't work for everyone, so I think I wanted to write (myself) permission to have taken steps to embrace my Otherness and just... find the people who got me, find the things I could love, find what else would work to make a life. I hope that's the same for any kid (of any age) who reads this.